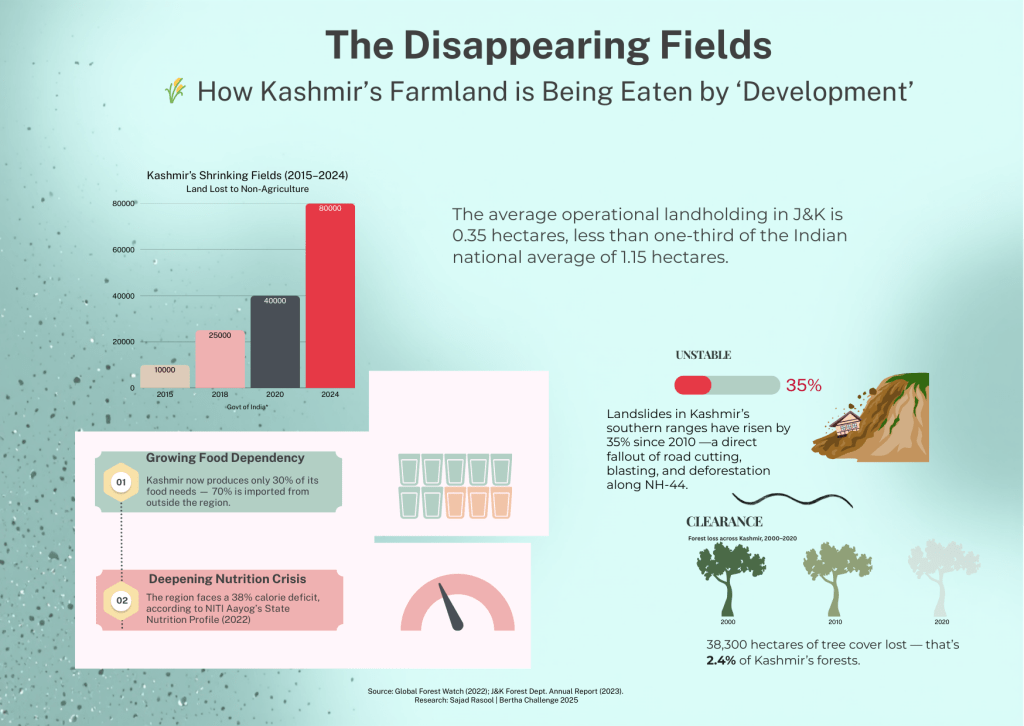

Each new roof replaces a patch of earth that can no longer breathe or grow. Shaban lives in a village at the foot of Kashmir’s only airport, the Srinagar airport, which is primarily controlled by the Indian defence forces. The airfield stands atop a Karewa, a fertile plateau that once nurtured rich soil and almond orchards before its conversion into an airbase. Gogoland, Rangreth, Kralpora, Wathoora, Buchroo, Lalgam, Panzan, and Gudsathoo. The conversion of agricultural land into non-agricultural use is accelerating, undermining not only livelihoods but also food security in the valley. Kashmir now produces only 0.45 million tonnes of rice annually, enough to meet just 35 percent of its domestic demand. The region faces a 38 percent calorie deficit, among the highest in India, and nearly 70 percent of households rely on imported food grains through the Public Distribution System.Where families once prided themselves on feeding the valley from its own soil, today they depend on supply chains stretching far beyond the mountains. 70% of rice consumed in the region is sourced from other Indian states, with most households dependent on Public Distribution System rations. The region currently produces only 30% of its food needs; local self-sufficiency has eroded as commercial returns from land outweigh the priority of growing indigenous foods.

According to the State Nutrition Profile of Jammu & Kashmir published by NITI Aayog, UNICEF, and IIPS (2022), the region faces a 38 percent calorie deficit, with average rural dietary energy intake measured at 1,897 kilocalories per person per day, well below the national rural average of 2,099 kcal. The report links this deficit to reduced local food production, dietary monotony, and growing dependence on imported food grains.

Gulam Nabi Bhat, a farmer in his mid-sixties from Budgam district, walks me through what remains of his fields in Wathoora village, at the base of the Damodar Karewa, the plateau that now hosts the Srinagar airport. The newly built Srinagar Semi Ring Road cuts directly through this landscape. Wathoora alone has lost around 225 kanals of prime farmland to the project. Gulam Nabi stops beside his small patch of surviving land, where, with the help from the horticulture department, he has planted a high-density apple orchard. He tells me he lost eight kanals (one acre) to the road construction. The remaining part of his land now stays waterlogged for months; the road’s elevated embankment blocks the natural flow of water, turning his field into a shallow pool after every rainfall.

Frustrated by years of neglect, Gulam Nabi filed a petition before India’s National Green Tribunal (NGT), challenging the Srinagar Semi Ring Road’s environmental clearances. His case, part of a broader complaint by local residents, argued that the raised embankment of the road had blocked natural water channels, flooding entire stretches of farmland. The Tribunal acknowledged the impact and directed inspections, yet on the ground, little has changed. The drainage remains choked, the crops still drown, and the dust from the road still settles on the leaves of Gulam Nabi’s orchard.

The road took my land once when it was built, he says, and now it’s taking it again, piece by piece, every time it rains

We used to grow mustard, paddy, and vegetables. This part of Budgam has always been known for its fertile soil, perfect for such crops. But over time, with the decline in irrigation and the changes in our geography, people began to see land only in terms of commercial value. We used to grow mustard, paddy, and vegetables. This part of Budgam has always been known for its fertile soil, perfect for such crops. But over time, with the decline in irrigation and the changes in our geography, people began to see land only in terms of commercial value.

Land that once fed our families for generations is now seen as a means to profit. With the commercialisation of agriculture, farmers have shifted to high-density apple orchards, hoping for quick returns; but it’s not the same.

This case is the first of its environmental petitions from Kashmir challenging post-2019 land-use changes on ecological and livelihood grounds. Semi ring road has been classified as a “strategic infrastructure corridor,” hence the project bypassed full EIA scrutiny under Category B exemptions; a legal loophole often used in “linear infrastructure” like highways.Pointing toward the highway and the dust settling on the leaves of his young apple trees, he says,

Look at this pollution – it’s killing what’s left of my farm. Nobody cares. I’ve watched this land change, foot by foot, into concrete: roads, malls, buildings that often stay empty. The land is vanishing fast, and I don’t know what it will look like in the years ahead.

I met Mohammad Afzal, another farmer who owns only a small patch of land now, barely enough to sustain. Most days he works at Gulam Nabi’s orchard, cutting grass to feed his cows.

The aerodrome you see up there,” he points towards the hill, “we had land there once, before it was taken for the airport back in the 1950s. Now, I go there only to look; it’s all fenced, all under the army

Wathoora, just fourteen kilometers from Srinagar’s city center, is emblematic of a larger transformation. Once a quiet farming village, it now sits under the weight of rapid urbanisation, where new housing colonies, shopping complexes, and overlapping road networks steadily consume what was once fertile ground.The farms stay in water by choked irrigation system and the road stands as a wall.